Today marks the 73rd anniversary of the famous radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds. In honor of that, please enjoy this in-depth piece on the 1953 movide adaptation.

In 1925, H. G. Wells sold the movie rights to The War of the Worlds to Paramount Pictures with the expectation that Cecile B. DeMille, the person at whose request the studio first acquired the property, would be the defining force behind its translation to the screen. Wells and DeMille met only once, in 1935, when Wells came to the United States while Things To Come was still in post-production. Wells had been lured into participating in the filming of his novel The Shape of Things to Come by producer Alexander Korda, who promised him virtual autonomy over its making. Wells’ experience on that film, although enormously frustrating for Menzies, its director, had given Wells hope that motion pictures might ultimately prove a viable medium in which to direct his creative energies. By the time of their meeting, at a party thrown in Wells’ honor at DeMille’s Tujunga Canyon ranch, DeMille had long abandoned any serious interest in making The War of the Worlds. In fact, as early as 1930 the studio had felt free to offer it to the great Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein to lure him to Paramount, but Eisenstein eventually abandoned the property, choosing instead to work on Que Viva Mexico, a film he started in 1931 but never finished.

Thus, it lay dormant at Paramount for two decades until, in 1951, George Pal, recently contracted to the studio as a feature film producer, discovered it and scheduled it for production.

It was to be Pal’s second film for the studio and his fourth feature-length motion picture since ceasing production in the late 1940s on the George Pal Puppetoons, a series of popular, Academy Award-winning short subjects. If staging the end of the world seemed too daunting for the creative resources and deep pockets of a Cecil B. DeMille, George Pal should not have even contemplated filming The War of the World. Yet, Pal’s rendition of that venerable SF classic was eventually recognized as one of his greatest motion picture triumphs and is widely regarded today to be among the best science fiction movies of all time. At the very least, sixty years after its original release, it endures as the definitive screen treatment of the alien invasion theme.

By the time Pal focused in on The War of the Worlds, it had already been scripted five times; one of those scripts had even involved Well’s son Frank, who was active at the time as a motion picture art director and production designer. Pal turned to London-born author Barré Lyndon, to draft a new screenplay that would update the story from turn-of-the-century Victorian England to mid-20th century America, and that would take into account the recent rash of flying saucer sightings. In fact, Pal envisioned that the Martian war machines, so integral to Wells’ story, rather than being the mechanical walking tripods of the novel, would resemble instead the flying discs that were being reported all across the globe.

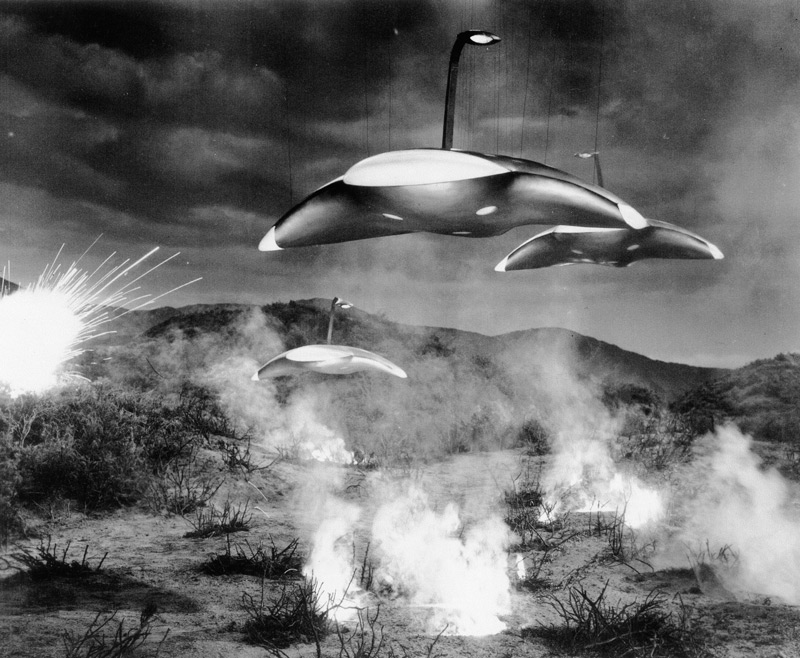

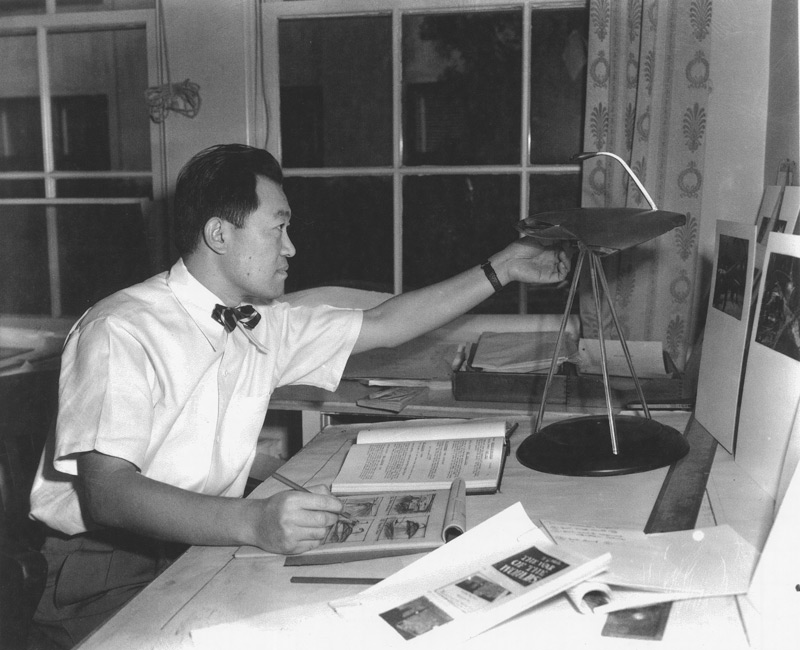

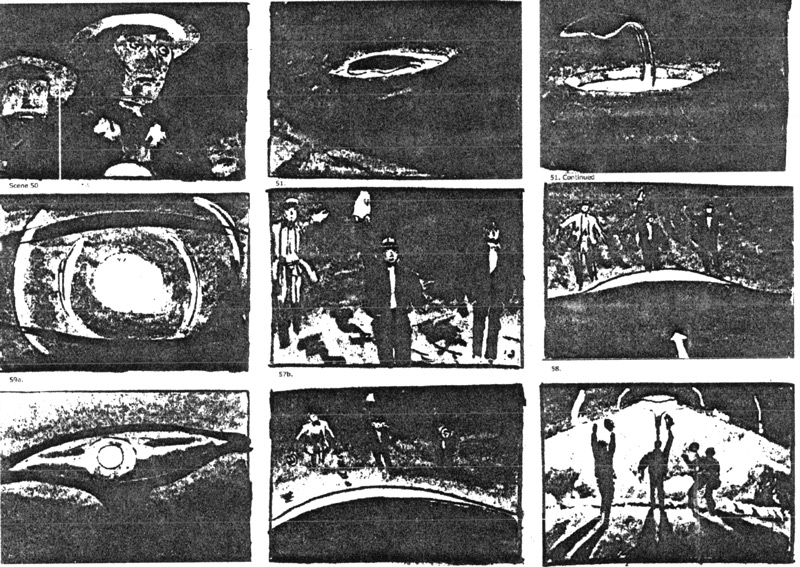

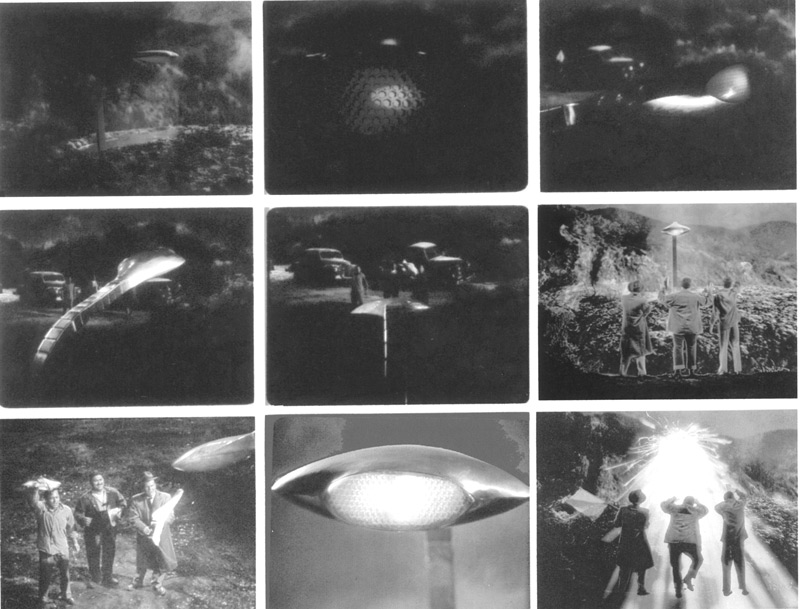

In an early pre-production sketch, artist Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986), who had worked previously with Pal on Destination Moon (Eagle-Lion, 1950) and When Worlds Collide (Paramount, 1951), suggested both the cobra head-shaped heat ray and the disc-like body of the war machines, without the three articulated mechanical legs described in Wells’ novel. Bonestell’s oil sketch, though loosely executed, seems to suggest two vane-like structures descending from the machine’s underbody. Under the supervision of unit art director Albert Nozaki, the basic concept of Bonestell’s sketch was further refined to show a disc suspended above the ground on three discrete energy beams. Although the appearance of the machines would continue to evolve, both the cobra-shaped heat ray and the suspension beams would remain essentially intact.

Born in Japan in 1912, Nozaki was the only art director of Japanese descent to occupy a major art directing position in the American film industry during its Golden Age. Like Bonestell, he’d studied architecture but discovered that finding work in that profession during the Great Depression was virtually impossible. He was hired as a draftsman by Paramount art director Hans Dreier in 1934, but was relieved of his job and placed in an internment camp during the Second World War. Immediately following the war Dreier hired him back and he made his way through the ranks to become a unit art director. An avid reader of science fiction in his youth, Nozaki naturally gravitated toward assignments such as When Worlds Collide and The War of the Worlds. For the latter film, especially, it’s quite evident that Nozaki was principally responsible for defining the overall look of the production. Later, as a freelancer, Nozaki designed several props for the well-regarded 1964 science fiction movie, Robinson Crusoe on Mars (Paramount); one of which was an interesting variation on his original manta ray design for the Martian war machines in George Pal’s film.

The War of the Worlds opens with a prologue. A narrator (Sir Cedric Hardwick), speaking presumably in the voice of H. G. Wells, reads from what is essentially an updated version of the original opening text of Wells’ novel. We are told that the Martians seek refuge elsewhere because their world faces climatic changes that endanger their survival. With that we are swept away on a grand tour of the solar system, thanks to the artistry of Chesley Bonestell and the ingenuity of Gordon Jennings’ special effects team. To create a convincing tableau of the stops in our tour, Bonestell’s paintings were combined with both animated and multiplane components. In all, Bonestell produced eight paintings for the prologue depicting various views of Mars, Pluto, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Mercury and the Earth. His depiction of the surface of Jupiter was perhaps the most elaborate. Painted on a four by seven-foot glass panel, the artist left openings in the art for the additions of flowing rivers of lava and plumes of smoke. The effect is compelling and the prologue, as a whole, sets the stage for the spectacle to come. As the prologue comes to a close we learn that the Earth, alone, of all the planets of the solar system, holds hope for the Martians to avert extinction.

Following the prologue, the sky brightens momentarily with the sudden arrival of a meteor as it plummets to earth. It falls on the outskirts of Linda Rosa, a small, prosaic town nestled in the Chino Hills of California. At its point of impact a brush fire flares, but is quickly brought under control. Three civilian deputies are posted at the site only to be disintegrated with the emergence of the Martians and soon the surrounding terrain is engulfed in a Technicolor onslaught of raging violence as the Martians advance in fearsome war machines. The machines are impervious to all earthly defenses and even the atomic bomb seems ineffectual in the face of the aliens’ superior technology.

Amid the melee, Sylvia Van Buren (Ann Robinson), a young library science teacher, and Clayton Forrester (Gene Barry), a nuclear physicist, are thrown together as they seek a means of escaping the Martian advance. Throughout the film Forrester’s comments, and those of his scientist colleagues, provide the audience with critical insights into the workings of the Martians and their enigmatic machines. Seeking refuge in an abandoned farmhouse, the couple is pursued by an electronic probe as more of the alien meteors fall to earth. In a face-to-face confrontation with one of the invaders, Sylvia and Forrester are given a fleeting glimpse of humanity’s strange and almost feeble adversaries.

All efforts to resist and contain the invaders fail and the Martians descend on Los Angeles as Sylvia and Forrester make their way into the city. There is a frenzied attempt to evacuate the populace, but the panic turns into mob violence and the two are separated and trapped in Los Angeles as the attack begins. Finally reunited in a church, Sylvia and Forrester embrace as a machine topples a nearby wall. Their deaths seem inevitable. But just when all appears hopeless, humanity is unexpectedly spared by the intervention of simple terrestrial bacteria to which the Martians have no natural immunities. Their mighty machines, once seemingly invincible, begin to fall from the skies as, throughout the world, the Martian invaders grow sick and die.

When The War of the Worlds premiered in Hollywood on February 20, 1953, the price tag on its production was around two million dollars. Reviews in late summer and early fall for its national release were highly favorable and some were outright raves. In the August 14th issue of The New York Times it was stated that, “The War of the Worlds is an imaginatively conceived, professionally turned adventure which makes excellent use of Technicolor, special effects by a crew of experts and impressively drawn backgrounds Director Byron Haskin has made this excursion suspenseful, fast and, on occasion, properly chilling.”

As one might well imagine, some seventy-five percent of its budget went into producing the film’s special effects. For its efforts, Gordon Jennings’ special effects team received the 1953 Academy Award, but Jennings himself succumbed to a heart attack in early January of that year, never knowing of the honor. Born in Salt Lake City, Utah, Jennings’ film career began in the early 1920s as a cinematographer and he started working in the specialty of visual effects in 1933. In that era before Academy Awards in the field of sound editing, The War of the Worlds also received the Motion Picture Sound Editors Association’s first annual award for “the most dramatic use of sound effects.”

For all the accolades and financial success that it enjoyed, the making of this classic film should have marked a high point in producer George Pal’s career at Paramount, but the fact is that throughout the entire production of The War of the Worlds, Pal was hampered by the studio’s management. Don Hartmann, who was in charge of production at Paramount, disliked Lyndon’s script (ironically, Lyndon had worked the previous year on Cecile B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth, the 1952 Academy Award-winner for Best Picture) and challenged Pal at every turn. Pal attributed completion of the film to the timely intervention of DeMille who convinced Y. Frank Freeman, the studio head, that the project was worthwhile. Even so, and in spite of Pal’s many successes, the film marked the start of the deterioration of Pal’s relationship with the studio. Over the next two years, Pal produced Houdini (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954) and The Conquest of Space (1955) for Paramount, but was unable to sell them on tom thumb and The Time Machine; films that he would eventually make for MGM, and for which his fame would continue to grow.

In the evolution of the American science fiction film there is perhaps no single individual who was more instrumental than producer George Pal. Born in Hungary in 1908, he studied architecture but was immediately drawn to the relatively new medium of the motion picture. His initial strength had been in a unique kind of labor-intensive stop-motion animation called replacement animation and his short subject films, mostly fantasies, eventually evolved into the Puppetoons. Pal produced forty-one Puppetoons for Paramount between 1941 and 1947.His first feature-length film, The Great Rupert (Eagle-Lion, 1949) was a comedy/fantasy about a fabulous dancing squirrel (originally intended to be a mouse), and it was soon followed by Destination Moon—the film widely acknowledged as having launched the 1950s SF movie boom. His later genre films include the now classic The Time Machine (MGM, 1960).

Frank M. Robinson, a best-selling author of both mainstream and science fiction novels, had his famous novel The Power produced for the screen by George Pal at MGM in 1968. In a recent e-mail to me, Frank reminisced about his involvement with Pal. Frank writes:

Met George a couple of times, but that’s about it. However There are interesting stories about the filming of The Power, et al. My last meeting with George was when Tom Scortia and I were shilling some project in Hollywood and we met Pal at the Beverly Hills Hilton (Hilton? Or just plain Beverly Hills Hotel? Memory fails.) It was toward the end of his career—he died in 1980 at age 72. The Power was his second to last film—he produced, Byron Haskin directed—with Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze ([Warner Bros.] 1974) being his last.

The Power went through two scripts by John Gay, a competent screenwriter (Separate Tables, Run Silent, Run Deep [both United Artists, 1958]). The first was pretty much the book. According to Ray Russell (former fiction editor for Playboy who migrated to Hollywood after he sold them [Mr.] Sardonicus [Columbia, 1961]), the first script was pretty much a slam-dunk—all Gay had to do was take the first few lines of every paragraph of dialog. Flattering, if true. The second script was written at the behest of its star George Hamilton. Unlike the downer ending of the book and the first script, Hamilton wanted a “walk-into-the-sunset-with his girlfriend” ending.

And Hamilton, to make a pun, had the power. He was dating one of the daughters of LBJ and the powers-that-be at MGM thought they could tap Texas money to fend off Kirk Kerkorian in his takeover attempt of the studio. Kerkorian won, and the rest is depressing movie history

Oh, yeah. On meeting Pal at the Beverly Hills Hotel, the first thing he said to me was, “Will you ever forgive me?” What a class act!

In addition to being a pioneer in the movie end of the genre, Pal was widely known as a kind and gentle soul, a rarity among Hollywood producers. In the late 1950s and into the 1960s he branched successfully from science fiction into fantasy with delightful and charming films like tom thumb, The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm and The Seven Faces of Dr. Lao (all MGM, 1958, 1962 and 1964, respectively). But if one Hollywood adage remains true above all others, it’s that you’re only as good as your last picture. Despite the unprecedented successes of his many films, his stock in Hollywood began to slip in the late 1960s and he eventually reached a point at which it became difficult, and in some cases, impossible, for him to generate the financing for his later projects. For those of us who dearly loved his work we’ll never know what could have been, but the fact remains, too, that we’ll never be able to forget what was.

As the bright red “star” of Mars rises large and luminous in the autumn sky I’ll no doubt look up and be transported back to those days so long ago when the world and I were young, the night sky was full of mystery and wonder, and we once dared to imagine what life might stir in the cool, dark spaces of that baleful, blood-red globe.

Vincent di Fate is a science fiction/fantasy artist who’s work spans decades. He has been heralded as “one of the top illustrators of science fiction” by People and has several mantles full of Lifetime Achievement awards from the SFF community.

I have to admit this is my least favorite of the 50’s SF films. I don’t like the religious overtones- as the humans take refuge in a church and pray, the bacteria that “god, in his wisdom” (admittedly a line fom the novel) has put on this arth go into action, killing the invaders. Having earth’s natural defenses take care of the invaders is one thing; having God take direct action against them is quite another.

I also didn’t like the redesigned war machines. I understand that having an articulated 3-legged walker would have been difficult at the time and would have to use stop-motion; nevertheless, the flying saucer design just didn’t stand out. Sure, It made sense more than a walking machine – but Wells could have described a flying machine or a wheeled one back in 1898 if he wanted to (the martians also had some flying machines at their disposal in the novel but they were not described in any detail) . The reason he went with a three legged walking machine was precisely because it’s something no sane human would even consider; it (and its 5-legged variant) contributed to the alienness of the invaders.

The reason he went with a three legged walking machine was precisely because it’s something no sane human would even consider

A point made with considerable force by Edward Hyde, IIRC…

This is once of the best scifi movies of the era. Gene Barry is good in most anything he does and, it maintains suspense and believability throughout. The girl is a whole lot wimpy but it fits the era. The martian war machines were great, and way cooler than the discription from HG Wells. Its 10 times the movie than the Spielberg version.

1 plot point in the novel that was left out of the Pal production, as well as all subsequent ones (AFAIK), was the use of poison gas by the Martians. This followed the destruction of 2 war machines by the British military. WMDs so lack visual impact. And they raise the question of why the Martians would use chemical weapons while utterly ignorant of biological ones. But it would have been nice to see the good guys land a couple of punches, even if ultimately irrelevant & at great cost.

A Northrop flying wing, the ancestor of the modern B-2 bomber, made a cameo appearance as the aircraft that dropped the ineffective atom bomb on the Martians.

The orgional novel was set in the UK during the close of the 19th century the 1953 movie which won a Oscar for Special Effects is in the 20th century but the deaths of the martians was the same they caught a cold a died